A Heritage Area and Local Nature Reserve

A Heritage Area and Local Nature Reserve

Introduction

The information below is taken from a CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST (CPAT) archaeological report written in connection with proposals for the Llanymynech Heritage Area Development Project.

It is an extensive report detailing the site, it’s historical past and status (then, 2004) of the site.

The report number is CPAT 618 and can be found on the internet if you wish to read further.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The general area around Llanymynech is one of considerable historical importance, containing a number of monuments of national significance ranging indate from prehistory to the early 20th century.

Prehistory

Llanymynech Hill is occupied by an impressive Iron Age, or possibly Late Bronze Age hillfort, the ramparts enclosing an area of 57ha, making it one of the largest in Britain. Archaeological investigationon the hillfort has so far been rather limited. In 1981 a section through the ramparts was recorded during construction work, which revealed the stone rampart and ditch of the inner defences, together with metalworking debris in the interior of the rampart dating from the 4th century BC to the 1st century AD (Musson 1981; Musson and Northover 1989, 20). A number of small-scale archaeological evaluations within the hillfort in recent years have revealed further evidence of occupation and metalworking, including part of an Iron Age roundhouse beneath the 13th green of the Golf Club which occupies much of the hillfort (Owen 1999).

The area to the west of Llanymynech also contains a number of other prehistoric sites, including the remains of several Bronze Age burial mounds and evidence for prehistoric land divisions, known as pit alignments.

Roman

The area has a long history of copper and lead mining dating back to at least the Roman period, and a hoard of 33 coins dating between 30 BC and 161 AD was found in a cave known as the Ogof, on top of Llanymynech Hill. It has even been suggested that the hillfort may have been the location for the last stand of Caractacus against the Romans in AD 49 (Jones and Mattingly 1990, 66-67).

The general area also includes a number of Iron Age, or Romano British defended enclosures or farmsteads, including a multiple-ditched enclosure just to the south of the canal (SJ 2698821103).

Medieval

It has been argued that the western defences of the hillfort were adopted as part of Offa’s Dyke, the 8th century linear earthwork which defined the boundary of the kingdom of Mercia. The precise course of the dyke through Llanymynech village is unknown although further to the south, around Four Crosses, it survives as an impressive earthwork.

Post-Medieval

Prior to the construction of the canal the area between Llanymynech village and Llanymynech Hill appears to have been largely agricultural, with small irregular fields and small areas of woodland. Traces of ridge and furrow cultivation, of medieval or post-medieval date, survive in fields to the south and east of the main Heritage Area. The Hill itself was unenclosed common land. This is the situation depicted by a map of the Bridgeman Estate in 1766 (Bradford Estate Papers) which indicates that the turnpike road between Oswestry and Welshpool, dating from around 1763, adopted a rather more sinuous route than the present road, with a side road leading into the village further to the east.

Industrial era (18th-20th centuries)

Ellesmere Canal

The waterway now known as the Montgomery Canal was built in stages between 1794 and 1821 and runs from the Shropshire Union Canal at Frankton Locks to Newtown in Montgomeryshire. The canal, which reached Llanymynech by 1786 at the latest, originally consisted of four distinct schemes which have only been linked together in name under modern ownership. Three of the schemes were specifically constructed to carry and distribute lime for agricultural purposes from the Llanymynech Quarries (Hughes 1983, 9). By 1840-41 there were 92 limekilns along a 26 mile stretch of the canal and a peak carriage of 56,501tons of limestone per annum was achieved (Williams 1989, 28).

In addition to limestone, the canal was also used to transport lead from the Tanat Valley mines of Cwm Orog, Craig y Mwyn and South Llangynog, as well as slate from the Llangynog area, which had previously used a river port on the Vyrnwy at Carreghofa.

The canal wharf at Llanymynech developed in association with the tramway system (see below). Originally, limestone would have been transported from the quarries to the canal by horse and cart, presumably being loaded onto boats moored along the northern side of the canal, close to the turnpike road, or a side road to the east. By 1806 the first tramway was constructed, associated with a small triangular canal wharf, with a second, larger wharf, lying to the east of the road. A third, longer wharf was added further to the west sometime between 1813 and 1858.

The Cambrian Railway’s Llanfyllin Branch was opened in 1863, and although at first the canal suffered little from railway competition (Morriss 1991) the railway eventually took much of the lime trade from the canal. The wharf was probably disused by around 1900, although quarrying and lime burning continued until 1914 (Hughes 1983, 157-8).

Tramways and Inclines

Following the opening of the Ellesmere Canal a system of tramways and inclines was developed to transport limestone from the quarry faces on Llanymynech Hill to the canal, where the rock was manually crushed before transportation. The earliest mention of a tramway is in December 1799 when a Mr Smith of Madely wished to lease land from the Chirk Castle Estate, suggesting that the quarry construct a railroad to the bank of the canal at an estimated cost of £100 (NLW, Chirk Castle 8528-8573). The first tramway to be constructed, however, was proposed in December 1804 and completed by June 1806. It was built by Arthur Davies, Robert Cartwright and Richard Jebb, who at this time leased quarries from the Chirk Castle Estate and a Mr West (NLW, Chirk Castle 6050 and 6061). It carried limestone from the quarry workings on land belonging to the Chirk Castle Estate to what was at that time the only wharf on the canal. A drum house is shown at the top of the incline, which carried a double track with a cross-over at the bottom where the lines joined a single track to cross the Welsh pool to Oswestry Turnpike road, below which was a small passing bay. The single track continued, possibly following the line of the side road noted above, to the canal wharf where it divided, with a branch running to each side of the wharf.

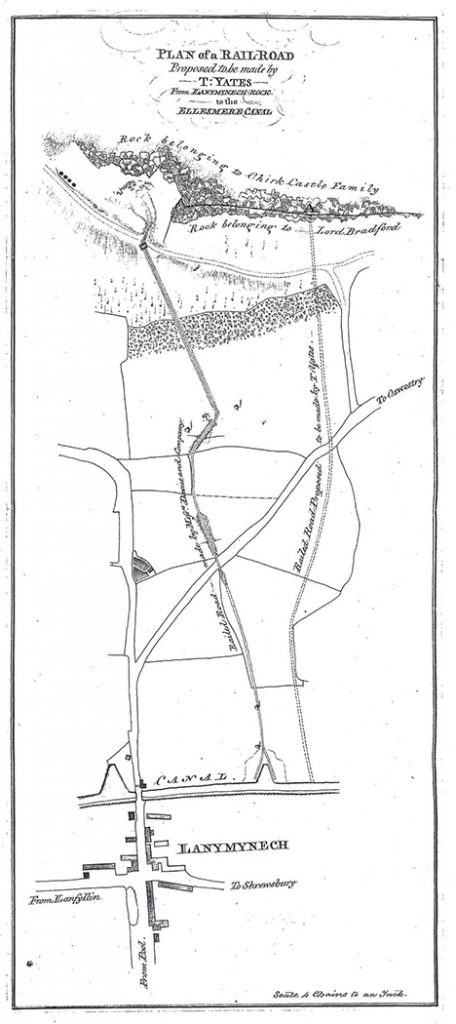

A second tramway was proposed by Thomas Yates in 1807, leading from land belonging to Lord Bradford to the canal, and is shown on a plan of that date (Figure 1; NLW Chirk Castle 6046). Although this was not constructed as proposed, it is probable that something was in place by 1810 when Yates started paying rent to the Bradford Estate (see below). One of the inclines was shown on an early version of the Ordnance Survey map in 1837 and this was to become the main transport route which, with later modifications, remained in operation until the closure of the quarry in 1914.

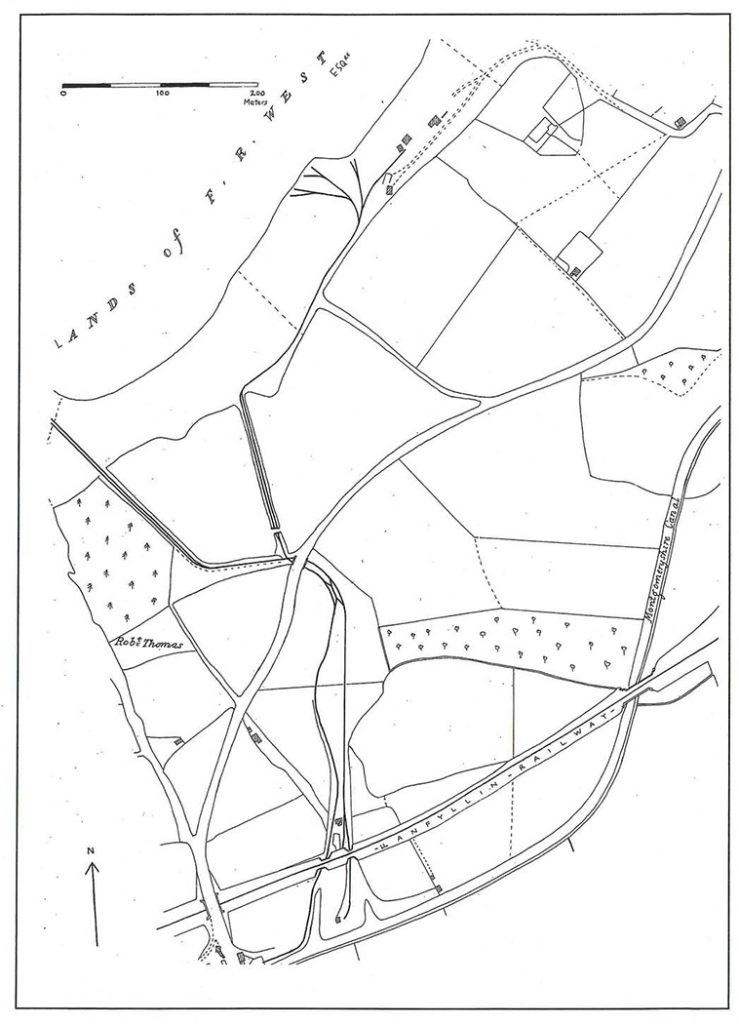

Cartographic sources for the early 1860s (e.g. Figure 2) indicate that by this time the earliest tramway had been abandoned below the incline, a new connecting track having been constructed to join the two tramways immediately west of the road, with a double line running beneath the road to a complicated cross-over, to the south of which the western line ran in a curve before heading to the western canal wharf. The course of the curve can still be traced in fields to the west of the Heritage Area. A building is depicted to the north of the canal wharves which is described as ‘House Stable Offices and yard, with a narrow strip to the south recorded as ‘Garden’. The building would appear to be in approximately the same position as that presently known as the stables, although the shape of the 1860s structure suggests that this is not the surviving building. The records of the Porthywaen and Llanymynech Lime and Limestone Works include a note that new stables were constructed to replace those burnt down soon after the formation of the company, around 1869 (R Hughes pers. comm.)

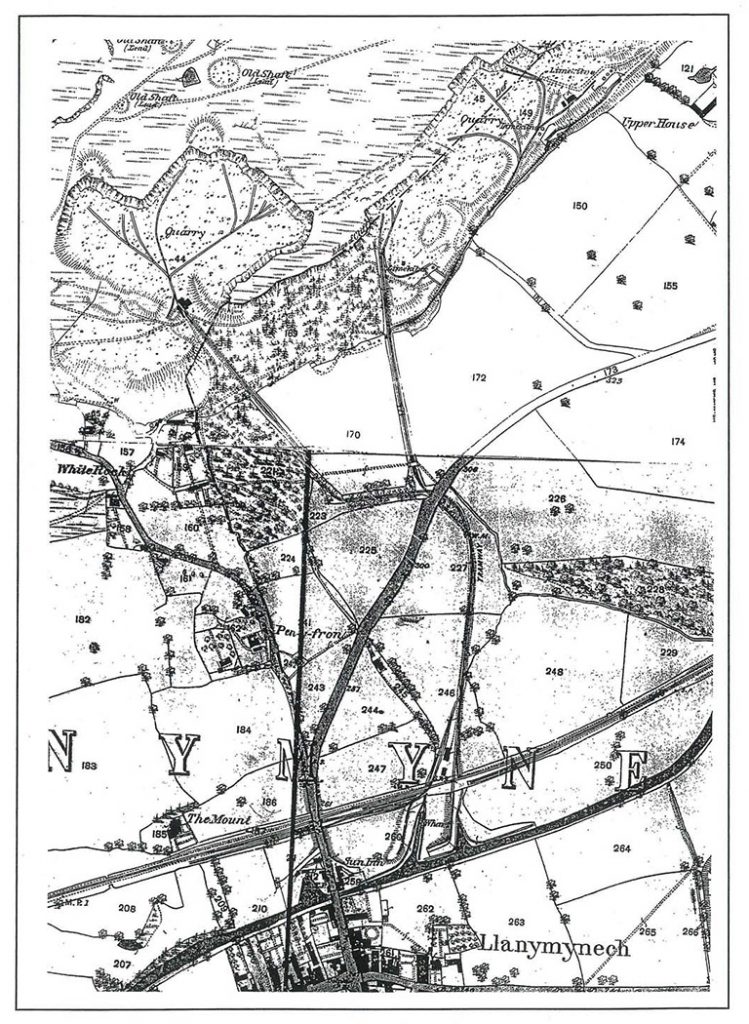

The tramway system during the later 19th century and early 20th century is well-illustrated by the Ordnance Survey 1:2,500 mapping. The first edition (Figure 3), surveyed in 1874, shows two tramway systems leading from the quarries to the canal. The western tramway system has a series of lines within the quarry workings leading to a brake house at the top of a Single-track incline with a short passing loop. The eastern tramway system has what must be an incline, although without a brake house, leading south from the quarry face, with a siding joining from nearby limekilns. A series of lines lead south-west from the eastern workings and limekilns to join the incline above the mid-point. As in 1863, both systems join near the road crossing, with a weighing station beyond.

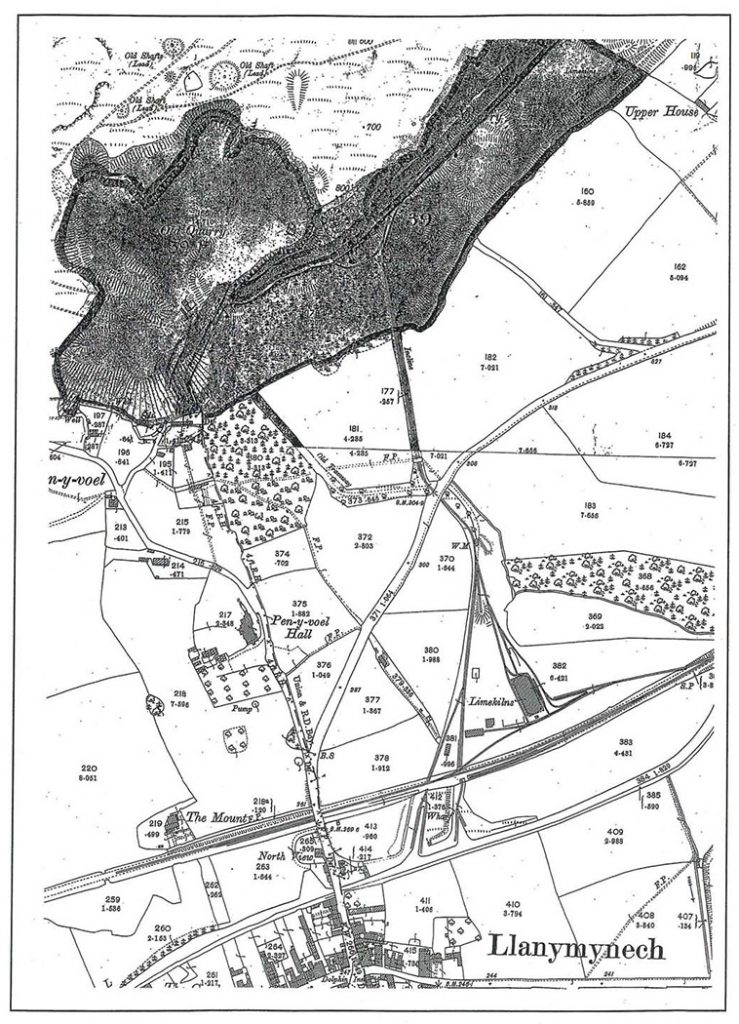

To the south the tramway continues as a double track which diverges to service both canal wharves, as well as joining the mainline railway, which opened in 1863. The second edition (Figure 4), revised in 1900, shows that by this time the tramway system serving the western quarry workings had been abandoned, while the eastern system had been much altered to include a double-track incline with brake house, with a new series of feeder tramways along the quarry face. At the southern end, the construction of the conventional lime kilns and their replacement by the Hoffman-type kiln (see below) had led to significant changes with a system of tramways and mainline railway sidings serving the later kiln.

Railways

In 1845 the Shrewsbury Oswestry and Chester Junction Railway was formed with the intention of constructing a line from the Shrewsbury to Chester railway at Gobowen, through Oswestry to Llanymynech. The line was only completed as far as Oswestry, in December 1848, by which time the company had been amalgamated with the North Wales Mineral Railway to form the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway, itself later absorbed into the Great Western Railway in 1854. Meanwhile, the London and North Western Railway had acquired the Montgomeryshire Canal Company and its tram roads and backed a scheme proposed by the Shropshire Union Railway and Canal Company to convert the canal into a railway. In 1855 the Oswestry and Newtown Railway was incorporated, with the line completed to Pool Quay by 1860 and to Newtown the following year (Wren 1968, 30-33).

The proposed route for the Llanfyllin Branch of the Cambrian Railway was surveyed in 1860, the resulting plan and schedule providing useful information regarding the existing layout of the canal, tramways and other structures at Llanymynech. Unfortunately, the quality of the plan precludes reproduction within this report. The line was constructed by Mr Savin and his brother-in-law, Mr Ward, and opened on 10 April 1863. A stipulation of the Act of Parliament allowing the construction was that the line was not to interfere with existing tramways by crossing them on the level and thus necessitated two bridges to carry the railway over them (Christiansen & Miller 1967, 29). At Llanymynech, a north-end bay platform catered for the Llanfyllin trains which, in order to surmount the canal, used the long ‘Rock Siding’ to a shunting neck, reversing on or off the branch. After several false starts and changes in company, a railway was eventually constructed from Shrewsbury to Llanymynech, and on through Llanyblodwel to the limestone quarries at Nantmawr. The single-track line, which bypassed the Cambrian line, was known as the Potteries, Shrewsbury and North Wales Railway, and was opened in August 1866 (Wren 1968, 34). Through traffic on the Rock Siding ended in January 1896, although it continued to serve the limekilns until their closure in 1914. After this the siding was used to store redundant wagons until the track was removed in 1939, the Llanfyllin Branch line itself finally closing in 1965 (Baughan 1991, 182-3; Cozens 1959).

Quarrying and limestone

The natural limestone outcrop has been exploited as a source of building stone for centuries. However, it was the use of lime as an agricultural fertiliser and in building mortar which led to large-scale quarrying during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Limestone is a form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3)which, when heated to between 900 and 1100°C is converted to calcium oxide (CaO), or ‘quicklime’, by driving off carbon dioxide (CO2), in a process known as ‘calcining’. Quicklime produces an exo-thermic reaction with water, forming calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2), known as ‘slaked’ or ‘hydrated’ lime. This will react slowly with the carbon dioxide and water in the atmosphere to revert eventually to calcium carbonate. It is this latter property which allows lime to be used as a cement, the quicklime being slaked with excess water to form a lime putty which, when mixed with sand, forms a pliable mortar which slowly sets hard. Although the use of lime in buildings was an important output for the lime industry, the main market was for agricultural lime, primarily used to reducethe acidity of the soil. An additional benefit was that lime also breaks down heavy clay soils, aiding drainage and assisting cultivation. Quicklime need to be slaked in order to produce a powder suitable for spreading, and this was usually undertaken in the fields by dumping it in heaps which were left to slake naturally. By the end of the 19th century burnt lime was being ground and sprinkled with water to form hydrated lime which was then dried and bagged for sale (Williams 1989,8-11).

Quarrying of the exposed limestone face on the southern side of Llanymynech Hill developed under a series of leases from the Chirk Castle and the Bridgeman Estates (later to be termedthe Bradford Estate when Bridgeman became Lord Bradford). The former held land on the western side of the hill, while the latter owned the eastern side. It would appear that the earlier workings were largely associated with the Chirk Castle lands and relatively large-scale operations were certainly under way by the mid-18th century. The earliest tramway is associated with these workings and it is possible that the coming of the canal provided the impetus for large-scale quarrying to develop on the Bradford Estate. Bridgeman’s rent accounts for 1766 – the first ones that are currently available – have a long list of disbursements, totalling more than £190, relating to what was termed the ‘lime account’, which suggests that the Estate was actively involved in extracting and working limestone and paying piece rates to local workmen. However, there are no comparable entries in subsequent ledgers, suggesting that the account had been closed and that the Estate had ceded its direct interests in limestone extraction to others.

The nature of the quarry workings may well have been influenced by the boundary between the Chirk and Bradford estates, which could account for the large promontory of un-quarried rock which divides the main workings. On the Chirk Castle lands, the method of working seems to have been by clearing benches and then removing rock from these until the floor of the quarry was reached at a depth of c. 50m, forming a large horseshoe-shaped quarry c. 270by 150m in extent. Further to the east, a linear quarry face appears to have been worked in a similar manner, the main workings extending for 250m, with a rock face up to 30m high. Between 1863and 1914 the rock face was cut back approximately 30m. Within the western quarry is an area of deeper working which appears to represent the latest phase of quarrying, associated with a tunnel cut through the promontory.

The limestone from the quarries was either burnt in kilns for use as a fertiliser or in lime mortar, or used in its raw state as a flux in the smelting of iron ore. During the Industrial Revolution the main centres of iron production in the West Midlands were at Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, and in South Staffordshire. The opening of the Ellesmere Canal, and particularly the connection to Birmingham with the opening of the Birmingham and Liverpool Junction Canal in 1935, greatly increased the market for Llanymynech limestone.

As the canal extended further, reaching Newtown in 1821, numerous limekilns developed at the wharves along its route. Although some of the limestone was burnt in kilns close to the quarry workings, the volatile nature of quicklime made its transport by water too hazardous and so much of the quarried limestone was crushed and transported to the various canal side kilns before being burnt.

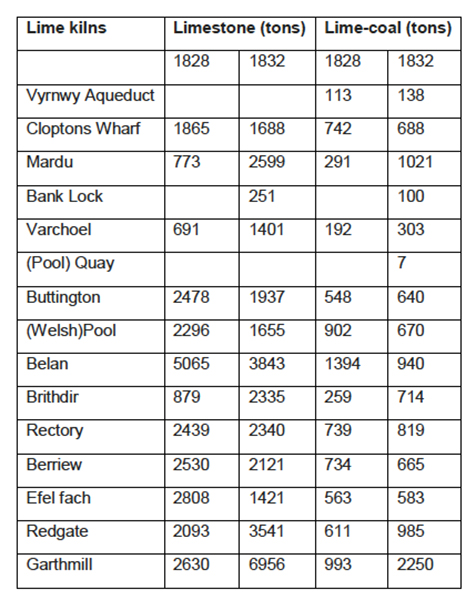

Records for the carriage of limestone to the canal side kilns south of Llanymynech are preserved within the Montgomeryshire Canal Report Books held in the National Archives in Kew:

Details regarding the ownership and operation of the limestone quarries and kilns is rather confused, although a series of leases from the Earl of Bradford and the Estate of Ruthin Castle shed some light on the matter. During the early 19th century the quarries wereevidently operated by two separate companies, each with a lease from one of the two estates. In 1798 Frederick West, of Ruthin Castle, married Maria Myddleton, co-heiress of the Chirk Castle Estate, who in 1819 was allotted a portion of the estate by the Court of Chancery, which may have included Llanymynech. Certainly by 1827 the lands formerly held by Chirk Castle Estate were owned and leased out by West, and by 1851 they had passed into the ownership of their son, Frederick Richard West (Ruthin Castle Estate lease). A leasing agreement of 1878 between the Right Honourable Orlando George Charles, Earl of Bradford, and William Cornwallis West, of Ruthin Castle seems to have formalised an arrangement dating from 1873 whereby West was granted a 99-year lease allowing him to transport lime from his quarries across land belonging to the Bradford Estate to the canal and railway.

The Chirk Castle quarries were initially run by Messrs Davies, Cartwright and Jebb, while Thomas Yates worked the rock on the Bradford Estate. Yates was paying rent to the Bradford Estate from 1810 to c.1830, while Davies, Cartwright and Jebb appear in the Bradford rental books after 1815 but were involved with Chirk Castle at least ten years earlier (see 3.12). Ten years later they were then superseded, or taken over by, Exuperius Pickering and Co, who continued to operate for about twenty years. In 1827 Pickering leased limestone quarries from Frederick West for 31 years and Pickering and Co were themselves replaced (or re-established) as the Carreghofa Lime Rock Co in 1844/45. Records from the Bradford Estate show that in 1835 Pickering and Co paid a rent of £15 5s for two railways and a stable, one of the former presumably being that run previously by Thomas Yates. In 1851 a seven-year lease of limestone quarries was granted by F R West and M West to Mr T E Ward of the Lodge, Chirk, while quarries on the Bradford Estate appear to have been operated by Mr Baugh. At the same time, it would appear that quarries were also leased to Longueville, Longueville and Williams, who themselves granted a further lease two years later to Joseph Needham and then in 1856 Longueville and Williams leased workings to Messrs Benjamin Manning and John Dicks. It would appear that Longueville and Williams were the Trustees of F M West and in 1863 they granted a lease to Thomas Savin, who was then described as a railway contractor, while by 1869 a further lease describes him as a limeburner.

In 1860 quarrying on the Bradford Estate was carried out under lease by the Carreghofa Lime Rock Company, with Waiter Eddy as Secretary (Plan of Llanfyllin Railway 1860). From the 1860s some of the quarries in the Llanymynech area seem to have had close links with the railways, being owned by Mr R S France in 1862, the secretary of the Mid Wales Railway (Baughan 1991, 27), and by Thomas Savin and Company, who was heavily involved with the Cambrian Railway and responsible for the Llanfyllin Branch opening in 1863. At this time, it would seem that Savin acquired the leases from both estates for quarrying at Llanymynech. Although Savin was declared bankrupt in 1868, his involvement in Llanymynech continued, with the company changing its name to The Porthywaen and Llanymynech Lime and Limestone Works, based at Cambrian Buildings, Oswestry. A statement of accounts to the company directors in August 1871 reports that a large number of limekilns along the canal at Newtown, operated by the North and South Wales Coal and Lime Company, had closed down and the construction of a number of kilns at Llanymynech was therefore considered as a ‘permanent and independent outlet for limestone’. In the late 19th century the company again changed its name to become the Porthywaen Lime Company Ltd of Llynclys, with Captain Nicholson as director. The company was still operating in 1928 when they acquired the Old Sun Inn at Llanymynech, which lay in the eastern angle formed by the canal and the main road to Oswestry, near the present entrance to the Heritage Area.

Quarrying was not the only activity on Llanymynech Hill during the 19th century as it appears that lead and copper miningwas still active, albeit on a small scale. In 1837 a 21-year lease was granted by the Hon. F West for mines and minerals to Messrs William Smith and James Williams. Two years later there was a deed of settlement between West and the Carreghofa Roman Copper and Lead Mining Company, principally Frederick William Smith, Edward Williams and Richard York.

Limekilns

The use of lime as a fertiliser may date back to the medieval period and lime putty mortars were used by the Romans and more extensively from the Norman Conquest. It is not known when the burning of limestone commenced at Llanymynech, although the earliest reference is a map of Chirk Castle Estate in 1753 which depicts what appear to be threebanks of triple kilns within the area of the quarry workings. The site of the kilns is not known, although they are likely to lie beneath extensive late 19th-century spoil tips. In 1754 the Reverend RichardPococke noted ‘a great number of lime kilns’ at Llanymynech, whilst travelling from Oswestry to Welshpool.

Although the raw limestone was clearly in abundant supply at Llanymynech, what made the area of particular significance was the relative proximity of coal from the Oswestry, Chirk and Ruabon coalfield. The southern end of the coalfield, between Trefonen and Morda, is only 6km from Llanymynech. The kilns at Llanymynech date from the main period of activity towards the end of the 19th century. By the end of the 19th century the use of lime in the construction industry was in decline with increased competition from Portland cement, which was both stronger and more water resistant, and this was undoubtedly a major factor in the eventual closure of the lime works in 1914.

The surviving kilns fall into two groups, one close to the quarry and the other near the canal and railway. The former group comprises three banks of kilns and associated structures to the south-east of the Wildlife Reserve, which are all variations of continuous draw kilns. They are depicted by the Ordnance Survey in 1874, along with a related tramway system, but had evidently fallen out of use by 1900.

A structure located on the canal wharf may originally have been a kiln and has a raised tramway leading to it. Its later use, however, was as a tally hut. The largest kilns at Llanymynech were constructed following the opening of the railway in 1863 and comprise two continuous draw kilns with single draw-holes and the later Hoffman Kiln, dating from around 1899.