INTRODUCTION

Since I began this study I have been surprised and alarmed at how quickly knowledge and memories of the local limestone quarrying industry have disappeared. When I began searching for information in 1979, I discovered only two men surviving in the area who had worked in the quarries above Llanymynech. Luckily, even though both men were in their eighties they still held some vivid memories of the brief spell they worked there as boys. Since I talked, with these men, both have sadly passed away – Bob Morris of Pant; in July 1983 and Cecil Corfield of Llanymynech, who died in April of this year (l984). With these men goes a vital link with the past – a thriving industry which only ceased seventy years ago. Many of the facts and stories contained in the following pages were told to me by these two men, there has been surprisingly little information from any other source. The odd photograph comes to light now and again but there are few artefacts to be found in the quarry or around any of the kilns, – much of the metal work – rails, trucks, wheels, etc. was taken away and used for the war effort.

The Quarry

You can approach Llanymynech Rocks from the lane opposite the café in Pant. [Café since closed – lane is by Methodist church]. The village itself is littered with small disused quarries which were privately owned, but by far the largest was the one owned by Thomas Savin who owned the Porthywaen Lime Company. This eastern end of the imposing rock face is perhaps the oldest part of the quarry. A tramway (now a footpath) leads away to cross the main road at the café, where it joins an inclined plane. At the top is a partly restored gin wheel the purpose of which was to lower loaded trucks of limestone down to a set of six kilns lying at the canal side. These were probably constructed shortly after the Montgomery branch of the Ellesmere canal arrived at Pant towards the end of the eighteenth century. They were abandoned well before 1895 as a painting shown later in the study shows. Before the arrival of the canal, lime stone was fired “on site” at the quarry or carted away to be burnt at the kilns elsewhere. Not all of the stone was burnt, much was needed for constructing canal tow paths or roads. A Mr. R. Davies a native of Pant recorded in the 1950’s his memories of the village in a period 1870-74. He wrote: “I wonder if there is still the same amount of quarrying and lime burning going on as there used to be. I don’t think so, as for one thing for a long period we made up a train of as many as 12 or 15 wagons of stone per day sending it via Llanymynech and the Potteries Railway to the Staffordshire earthenware works and I am told it is not used now, and there always seemed then to be work for all who could do it in the quarries, if bad weather didn’t stop it”.

In front of the cliff face there is a patch where one a tramway ran. In dry weather the grass grows better where the sleepers once lay, and the course of the track can be clearly seen. From here the scale of quarrying becomes obvious. The vertical cliff rises to almost 200 feet in places and is made up of horizontally bedded carboniferous limestone. All of these beds were given names in Welsh or English by the quarrymen after their colour or size. One, quarried for flux in the iron smelting process was called the “Flummery- Red”. They all vary in texture from coarsely crystalline to finely grained compact limestone, and they all vary in depth. One of the largest beds is 13 feet thick and lies about 30 feet up the face.

About 150 men were employed in the quarry during the summer months but this figure dropped to around 50 during winter, who would be employed cutting and dressing building stone. The weather, it seems, played a determining factor as far as employment was concerned. Bob Morris was only 13 when he started work at the quarry in 1912. He was called the “nipper” and would be employed leading horses and trucks to and from the winding gear or taking tools or messages from one part of the quarry to another. For this he was paid a mere five shillings [25p] a week, and when he happened to enquire about a rise on his 14th birthday the reply was that the only rise he would get would be up the cliff face! This must have been enough to keep him quiet for a while for the men working on the cliff face drilling shot holes were often suspended on chains anchored at the top of the cliff. The days must have seemed long since their working day was from 6.50 a.m. to 5.50 p.m. on weekdays, 6.40 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. on Saturdays with Sunday as a day of rest. Only one set of workers, the packers down at the rotary kiln at Llanymynech operated on a shift system, working through the night to keep the kiln fed.

After the drillers had performed their task, the explosives were set, the fuses were lit and a section of rock was blasted from the face. I have been told that black powder was used for this purpose, being not as “violent” as dynamite. However, I remember as a child discovering a box of strange looking white sticks beneath the surface of a pond in a disused quarry above the Powis Arms public house. I can still vividly remember the label when I drew a stick from the box – it said “Polar’s Anon Gelignite”.

Whatever explosives were used, they were kept in a powder store in the top quarry. Hewn from the rock, it is a small rectangular room. One man would be in charge here and he would have a team of men working for him. Unfortunately, there was once an accident at the Porthywaen quarry when a spark from a quarryman’s hob nailed boot resulted in the powder magazine exploding.

With the blasting over it was time for the stone breakers to move in. Mr. Morris remembers these workers being on piece work, in other words paid for the quantity of rock smashed up. Occasionally large boulders were taken away in one piece and taken by rail to the Welsh coast where they were used to protect the railway from the sea.

The rocks were taken from the face to the gin wheel in large rectangular wooden trucks. The only two remaining trucks or vans on the site now are small V shaped side tippers used to tip the rubbish or raffle into heaps away from quarrying operations, although it was also used in the construction of canal towpaths. More than one letter complaining about the quality of this raffle was sent by the Canal Company. At the top of the inclined plane, which ran down to a huge line kiln at Llanymynech, four trucks at a time were hitched together at the gin wheel. Bob Morris sometimes had the job of “brake boy” – making sure the trucks were securely hitched before their journey down the line began. Halfway down the incline was a trap, a safety feature which meant the trucks would be stopped unless a lever was pulled to let them pass. It was fortunate that this mechanism was installed since Bob once made an error of judgement and four trucks of limestone went crashing down the line to hit the trap, cascading stone down the main road. One wonders if Bob got his five shillings that particular week since it was the rule that any tools broken or lost were paid for by the quarryman responsible!

Occasionally in cold weather the “nipper” was sent down to the kiln by the men in the rest room at the side of the gin to fetch a bucket of coal for the fire. Bob recalls riding back up the incline on the train of empty trucks and if he was quick enough, he might earn a halfpenny for his troubles.

Another feature of interest in the quarry is the Blacksmith’s shop which now lies derelict under vegetation. Its blackened end wall clearly shows where the blacksmith stoked his fire. He would have been responsible not only for shoeing the horses which were used to pull trucks around the quarry, but also for the upkeep and repair of all the quarry tools; drills, picks, hammers, nails, etc. The horses used in the quarry and at the kiln were stabled at the rotary kiln [the Hoffman]. Again, the stables are in a dilapidated state but looked capable of housing five horses, some of which were led up to the quarry each day and back down in the evening. You can still pick up pieces of discarded leather harness at the kiln site, – one piece of harness found yielded a brass nameplate with the name “Pierce, Saddler Llanymynech” engraved on it.

Mr. Corfield remembered that Harry Herbert was the horseman in the quarry.

Llanymynech Hill

Llanymynech Hill forms the southern end of a limestone belt which extends as far as the Great Orme at Llandudno, North Wales. It is situated five miles from Oswestry on the Powys Shropshire border. In fact, the greater part of the hill is in Powys, but following the line of Offa’s Dyke which skirts the hill, it is clear that at one time it lay on the English side of the border. Offa’s Dyke follows the precipitous northern and western slopes, in places disappearing altogether where there is obviously no need for a man-made defensive structure.

Quarrying operations began relatively recently, but mining, mainly for copper and lead ores was probably started even before the Romans arrived. Certainly, the hill is recognised as being a hill fort during the Iron Age, and there is no reason why the people of that time should not have known about the mineral potential of the hill. But it is the Romans who have left us the first real evidence of mining operations, principally at the cave system known as the ‘Ogof’. Here, various Roman artefacts have been recovered over the last few centuries, many however have unfortunately been lost. The most recent find was 35 coins found in 1965 by a group of schoolboys from Oswestry. The coins are on permanent display at Oswestry library [no longer on display in Oswestry]. It appears that copper was mined at the Ogof, although to the north of the cave is a series of open cast pits from which the Romans probably extracted lead ore. The search for these and other minerals, such as calamine continued up to the late 19th century. My particular interest in Llanymynech Hill however, lies in the quarrying of limestone which has undoubtedly made the greatest mark upon the landscape – with the possible exception of the golf course!

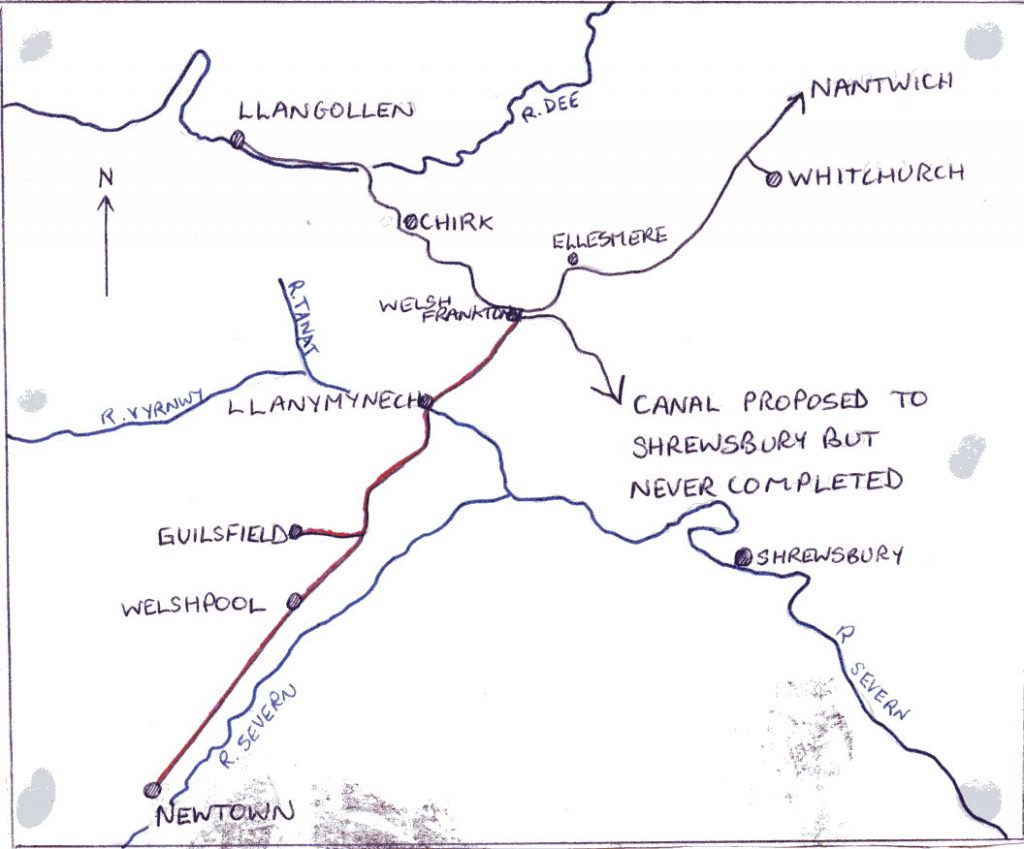

The Montgomery Canal

At this point, the Montgomery Canal deserves some consideration. The branch to Llanymynech from the Llangollen Canal at Welsh Frankton was built specifically to reach the valuable limestone rock at Llanymynech. Work began in 1793, and by 1797 it had extended beyond Llanymynech to Garthmyl through Welshpool. By 1821 it reached its final destination of Newtown – a total length of 33 miles.

The arrival of the Montgomery Canal gave a boost to the already thriving limestone industry. Farmers in neighbouring counties were crying out for lime to spread on their fields, and now it could be delivered much more efficiently. A horse could now pull a 55 tons load behind it instead of under 1 ton by road. The canal also provided a route to the Black Country where lime was needed as flux for the smelting of iron. But before joining the canal network at Welsh Frankton, every loaded boat would be charged a toll at the office next to the lock system there. The amount was decided by an index strip fastened to the side of the boat at water level. The lower the boat lay in the water the heavier the toll. In this way the canal company could recover some of the cost of building the Montgomery branch.

Apart from the advantages of transporting lime and stone away from the quarries at Llanymynech, the canal meant that coal and machinery could be brought into the area.

Coal was probably provided by Owen of Pant who at one time owned a canal boat called ‘The Five-Sisters’, so called because Sam Owen’s wife had five-sisters. The Owens still run a coal business in Pant, and it seems a tradition that the name Samuel be kept in the family, the present generation of sons having retained the name of their father and grandfather.

During the autumn of 1796 the first boats laden with lime made their way towards the Ellesmere Canal system and a new era of prosperity was born. In the next 70 years the population of Llanymynech doubled.

Early Limestone Quarrying In The Pant/Llanymynech Area.

Quarrying for limestone at Llanymynech Hill began many years ago. Amongst the diverse occupations of the people to be found in the Parish registers the word ‘limeburner’ appears as far back as the mid 18th Century. In later years ‘limeman’ can be found, as can the word ‘labourer’. However, this loose term could also include farm labourers, roadmen and the like.

Evidence of some of the oldest quarrying and lime burning can be found at Pant. Not all quarries here sent limestone to be fired, some provided stone for roads, or for the towpaths running alongside canals. The quarries themselves are well hidden now behind a century’s growth of vegetation. Occasionally, a quarryman’ s boot or even a piece of horse harness can be found, and it’s still fairly easy to trace the paths of inclines and tramways, which used to carry trucks of limestone to local kilns or the Montgomery canal. The way in which these trucks travelled up and down the inclines deserves some explanation.

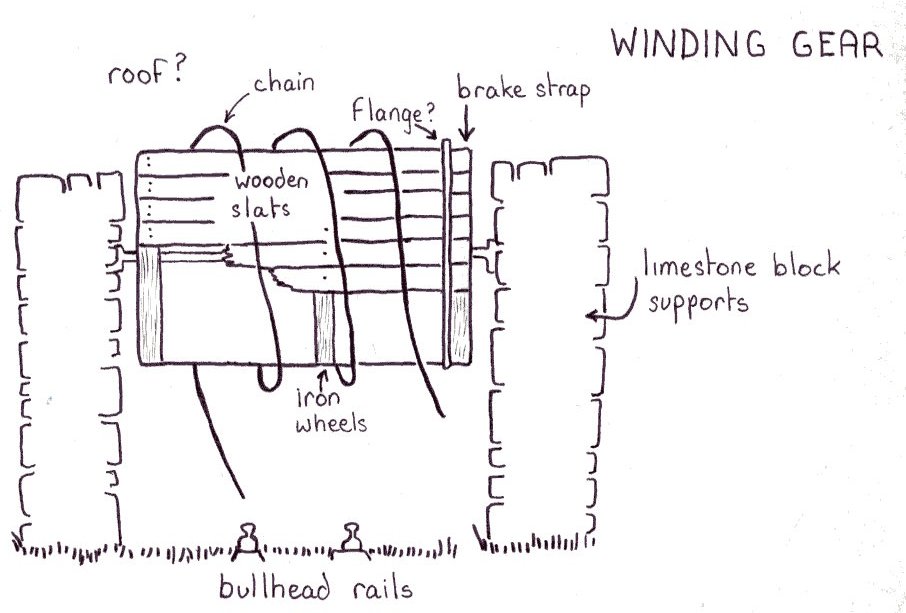

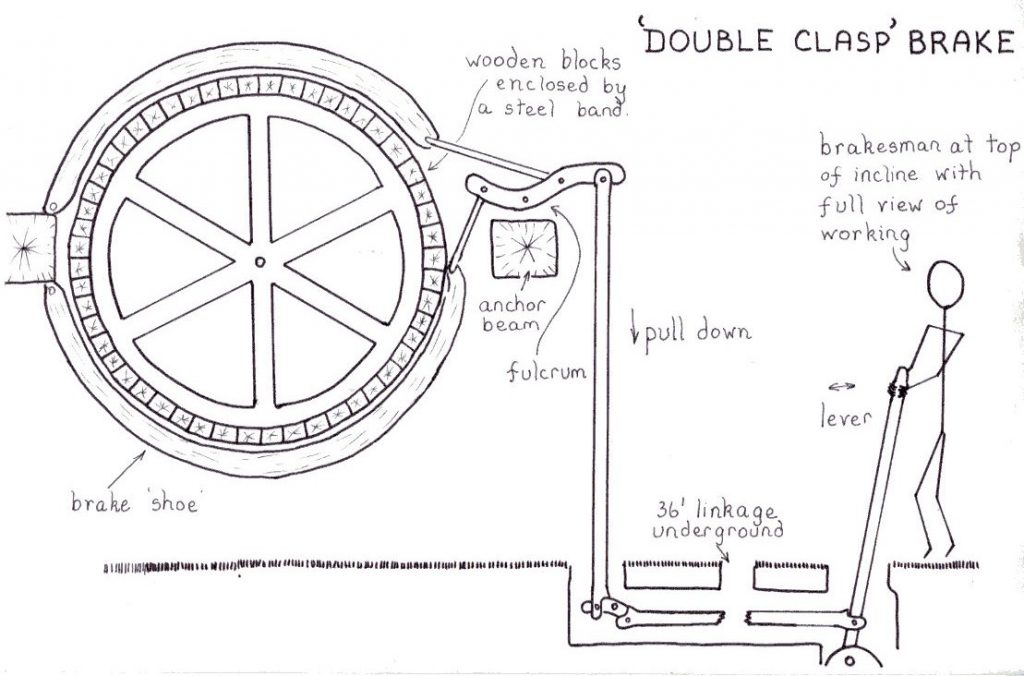

At the top of an incline was a large rotating wooden drum with either wire rope or chain wound around it [see Figure 3]. Trucks containing limestone were hitched at the top of the incline and let down, their speed being regulated by two factors; firstly, a huge brake (the mechanism of which can be seen in Figure 4), and secondly the weight of empty trucks coming back up the incline. At the bottom of the incline the full trucks would be emptied then hauled back up by the weight of full trucks coming down. The quarried limestone would then be either fired, in kilns, or loaded straight on to barges, then taken away by canal to be fired somewhere else or to be used directly as a hardcore for the construction of roads or towpaths.

Fortunately, at the date of writing, there are still several men living who have worked in the old limestone quarries of the area. One living in Porthywaen, and who once worked at the quarry there, described in detail the process of firing the old ‘inverted bottle’ type kiln:

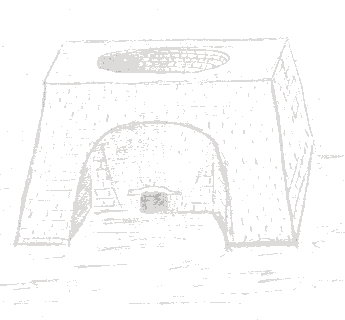

First of all, planks would be placed over the draw hole [hearth], then brushwood and kindling thrown down from above. Alternate layers of limestone and coal were built up to the top of the kiln, loaded of course from above. It was important to judge the correct ratio of limestone to coal otherwise the lime would be spoiled. House coal was placed at the draw hole which would burn the planks and so begin to fire the kiln’s load. The whole process took two to three days and was complete when the fire had reached the top of the kiln. The finished lime was then shovelled out from the bottom of the kiln through the draw hole. The wheelbarrows which took the lime from the kiln held approximately one to one and a half hundredweight so a limeburner could measure roughly how much came out of the kiln. The tallest kilns in the area produced about 30 tons per fire.

Sketch of ‘inverted bottle’ kiln shown below:

Structure Of The Kiln

At the turn of the century there was a demand for finer lime than the familiar inverted bottle shaped kilns could produce. It was decided to build a superior type of kiln at Llanymynech which could provide lime by firing with less coal therefore producing a finer lime for industry. The Hoffman kiln today is very much overgrown. Plants such as ferns, mosses, nettle and ivy have taken a firm hold on it and there are even a number of sizeable lime trees on and around the site.

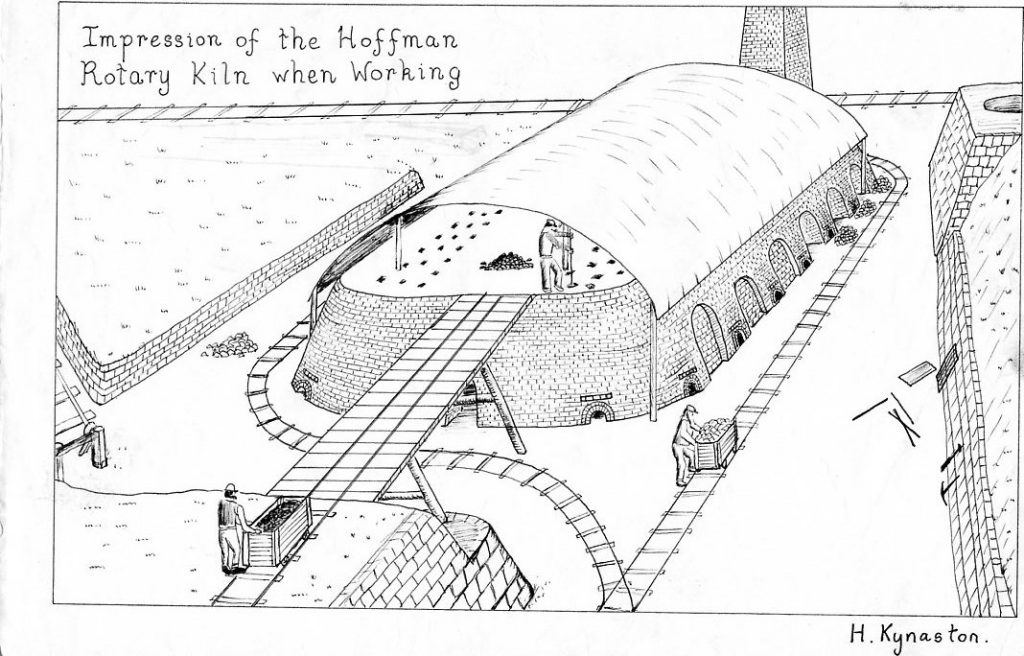

Despite this ever encroaching vegetation, the condition of the kiln is remarkably good. Its oval shape with steep sloping sides has a circumference of approximately 110 metres and each long side has a length of 40 metres. At one time the entire kiln was covered by a curved galvanised roof, but this has long since disappeared, leaving a total height from the present-day floor of about 4 metres or 40 layers of bricks. While counting these layers it was interesting to note that each layer alternates, having bricks lying end on then side on and so on.

At one end of the kiln (nearest the canal) stands a tall square section chimney approximately 30 metres high which took the smoke away from the area and probably served the purpose of “drawing” the draught through. Over the years its double skin of bricks has weakened and now it is supported by an iron brace.

Along each side of the kiln are 6 arches 1.25 metres wide and 2.20 metres high and they provide entrance to the formidable interior in which stands a long central pillar to support the roof. In the roof can be seen small square holes spaced out at regular intervals. The function of these will be discussed later.

To the left hand side of each arch is a draught hole 90 centimetres wide and 80 centimetres high leading into the kiln and also beneath its floor.

Approaching the site from the A483 one can still catch glimpses of the sleepers and rails of the tramways which served the kiln with trucks carrying limestone or coal.

It has already been mentioned that this structure was intended to produce a finer lime at the turn of this century. It is one of only a few in the country, if not Europe, and by looking at the 1.70 metre thickness of its walls, it was surely built to last. And yet the Hoffman kiln closed down in 1914 and was therefore only in production for about 20 years. Why this was so is one of many unanswered questions. Perhaps one or all of the following possible reasons led to its closure:

- Complaints of smoke

- Better quality limestone at Porthywaen

- Outbreak of first world war

- Poor maintenance and deterioration of the canal

- The Hoffman kiln never performed well

Functioning Of The Kiln

There are several speculations as to how the kiln actually worked. It is certainly different from the “inverted bottle” type kiln in that limestone is loaded through its arches and not from above.

Coal (presumably a slow burning anthracite) arrived by horse drawn barge on the nearby Montgomery canal, now a branch of the Shropshire Union canal, and was poured into the kiln through holes in its roof by the firers.

There are several holes to each section of the kiln but before coal was poured into them iron rods were held in position through the holes so that the packers beneath could skilfully build a stack of limestone rocks around them. Occasionally, a rough built stack would collapse and the entire structure would have to be built again. The limestone loaded trucks which descend on an incline from the rock face, arrived in pairs and were probably pushed around the kiln until they arrived at the correct arch. There they would be swivelled through 90°, run on temporary rails into the kiln and unloaded. From the scanty evidence of existing trucks, it is difficult to say exactly how they were unloaded. The type of truck can be found under the rock face and also the type of tipping mechanism employed. However, these trucks were relatively small, and it could be that a larger rectangular truck which had one side left open was used for travelling up and down the incline.

It is known that each section through its respective arch was packed and fired in succession rather than every section packed and the whole kiln fired. In this way there was a sort of rotation – as one kiln was smouldering, another was being packed and another was being raked out. Their timing was such that by the time the workers had completed one “lap” the first section would be ready to rake out. One wonders how long the whole process took, – twelve hours, a day, three days? Again many questions still remain unanswered.

Surveying the now overgrown kiln shrouded in its green canopy it is difficult to get an impression of the working conditions that the men must have endured. The first factor that springs to mind when considering a modern busy industrial concern is noise. But would it have been noisy working at this kiln or indeed any other? What sounds would one hear? A steam engine from the adjacent kiln, the rumble of trucks descending the incline, the occasional steam train, the odd blast from Llanymynech rock but certainly little mechanical noise.

There must have been more uncomfortable aggravations than noise. Dust for instance, heat certainly, and although the tall adjoining chimney must have carried much of the smoke away, there was probably a constant stench of burning to anyone in the vicinity.

It is hard to believe, walking round the kiln, that men actually worked here. Conversely, I am sure it would have been difficult to convince a worker in the heyday of the kiln that in seventy year’s time, cows would be meandering in and out of it and trees would be growing on top. With this in mind, below is a poem entitled “Thoughts of a Kiln Worker”:

Another long shift, the kiln needs to be fed

That same pall of smoke lingers grimly overhead.

The distant rumble of trucks on the line

Signals more hard graft, more dust and grime.

But it won’t be for long (or so it’s been said)

Till the old girl’s cold and the workings are dead,

Well, it doesn’t matter really, I’m getting on now

But I can’t see it closing somehow

With all this work? They’re begging for lime-

This place’ll be alive for a long, long time.

No end of rumours have reached my ears

But this stack’ll be smoking in a hundred years.

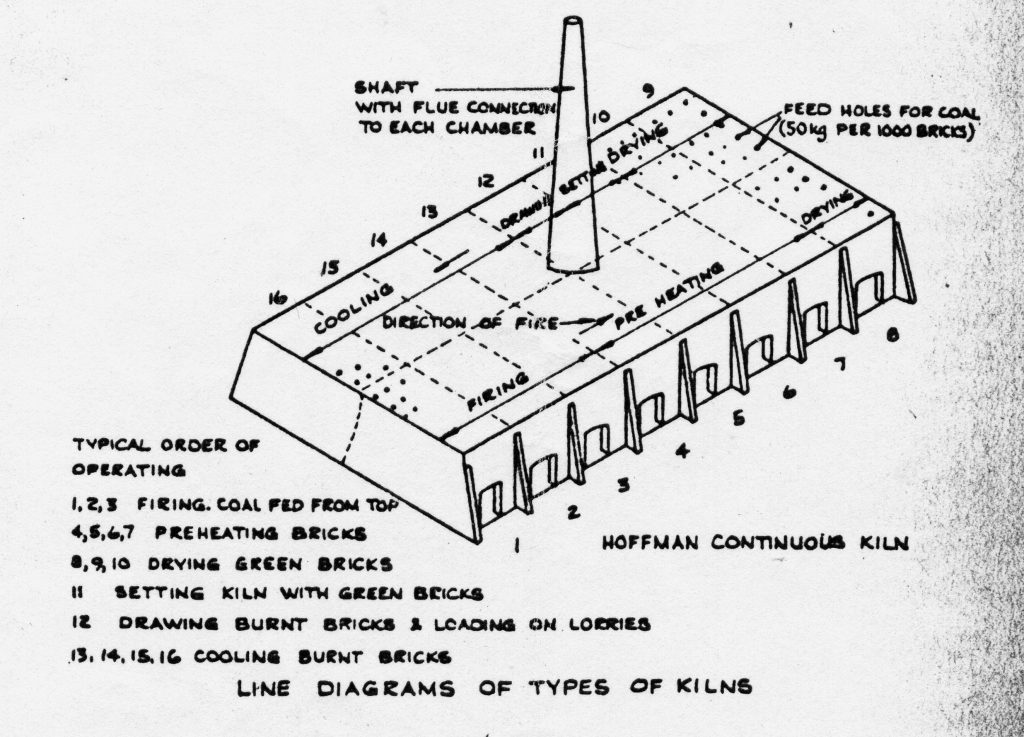

The following diagram and text are from an unidentified document. The description relates to the use of the Hoffman kiln for brick making but the principle of a ‘continuous rotary burn’ applies to the lime kiln.

Hoffman kiln

This is a continuous kiln, that is, the fire never goes out as it is transferred from one chamber to another. To facilitate loading and unloading, the kiln is divided into a number of separate chambers, usually 16, having 8 on each side with dampers between them which may be opened for the fire to pass from one chamber to the next. All the chambers in one kiln are connected to a single chimney shaft. As the fire passes round the kiln so the chambers in front of the actual firing zone are gradually warmed, and the chambers behind cool off slowly. Although the burning time is only about 3 days, the bricks are in the kiln for about 10 days to allow for raising the temperature and, after burning, subsequent lowering of the temperature before unloading the chambers.